NSW Far North Coast & Northern Rivers flood impact research, March 2022

- Briefing Note 466

Introduction

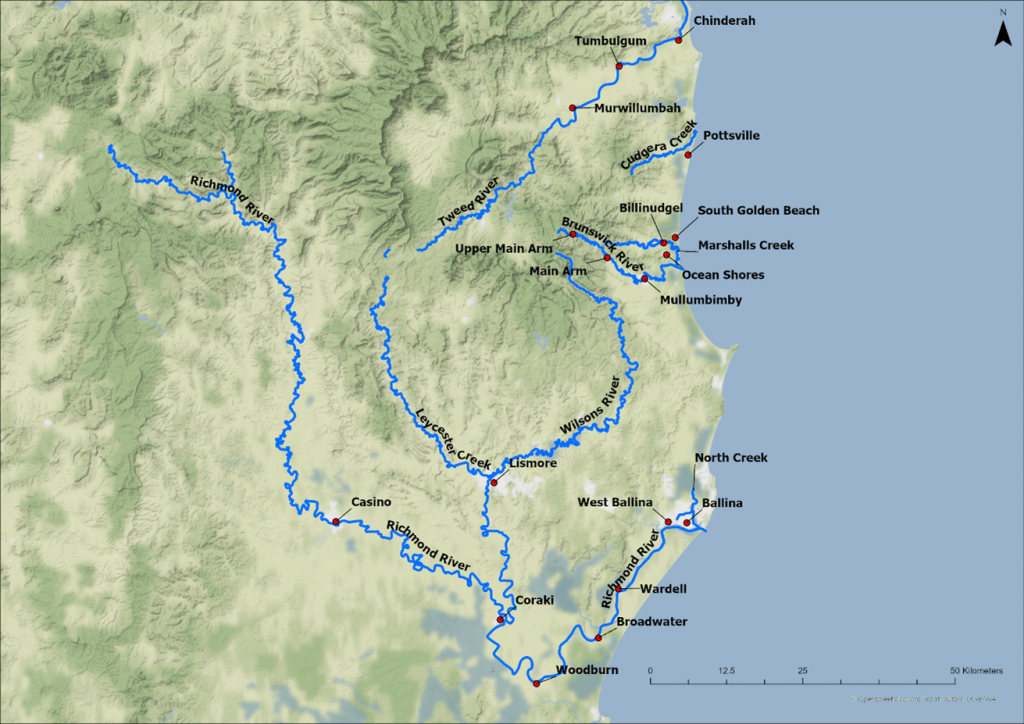

Between the 25th of February and 2nd of March 2022, a series of severe rain and flooding events impacted the east coast of Australia, stretching from the Sunshine Coast in South East Queensland to the South Coast of New South Wales. In New South Wales, the Northern Rivers region (Figure 1) was severely impacted, with the Tweed, Brunswick and Richmond / Wilsons River catchments experiencing severe flooding. Almost three weeks after the flood, Risk Frontiers undertook a post-flood research visit to the area.

Overview

On the 17th of March 2022, Risk Frontiers deployed teams to the Northern Rivers and Far North Coast regions of New South Wales to observe and report on severe flooding in the area (Figure 1). The teams visited severely flood-impacted towns and rural areas in several catchments including:

- Richmond River and Wilsons River catchments (including Leycester Creek) – Key locations include: Lismore, Casino, Coraki, Woodburn, Broadwater, Wardell West Ballina and Ballina (Figure 2).

- Tweed River and Brunswick River catchments (including Marshalls Creek) – Key locations include: Murwillumbah and South Murwillumbah, Mullumbimby, Main Arm and Upper Main Arm, Billinudgel, Ocean Shores and South Golden Beach (Figure 14).

The survey teams spoke with residents, business owners and volunteers in impacted areas and recorded the observations of impacted residents and business owners. The teams also recorded flood depths, noteworthy structural damage to built assets and geomorphic impacts in rural areas.

Key findings

Community leadership – Community leadership was observed in many locations, with community recovery hubs established in informal locations such as community halls to assist communities with their immediate recovery needs. These were in addition to formal government recovery mechanisms.

Warnings – Residents in all locations reported using a patchwork of sources (Facebook, community groups, phone calls and SMS from friends, radio and SES emergency messaging) to receive information on rising water levels, expected peaks and evacuation messaging.

Without exception, residents in all areas visited expressed alarm at the speed with which water levels rose and surprise at the ultimate height of the floods. Residents expressed dissatisfaction with the limited frequency of warnings as waters rose quickly and perceived that peak heights had been underestimated. There were also reports of emergency services not using public warning sirens. Some areas received limited warnings due to telecommunication outages (e.g. Mullumbimby).

In some cases (e.g. Lismore), even if residents and businesses were provided enough time to move stock, they likely would have found their preparations ineffective due to the extreme water depths. It is clear, though, in some locations (e.g. Murwillumbah CBD), residents and businesses had saved some possessions. The exact extent would be useful to learn to assist in measuring the overall financial benefit of warning systems.

Community behaviour – Many people did not evacuate and in some instances subsequently required rescue. Such behaviour was also evident when Risk Frontiers visited Lismore after the 2017 flood. Emergency services again were faced with the challenge of preventing people from driving into flood water.

Caravan parks – The long-held theory is that it should be possible to evacuate dwellings in caravan parks in a timely manner prior to flooding; however, many have evolved to be semi permanent and fixed in place. Many caravan parks across the Northern Rivers have suffered severe damage. These floods have again highlighted the vulnerability of caravan parks and their residents to flooding.

Infrastructure resilience for telecommunications – Most areas experienced power and telecommunication failures of NBN, ADSL, mobile and landlines to some extent. In many areas, these services still had not been re-established after two weeks. The ability to rapidly re-establish communications with isolated communities and individuals was dependent on the availability of generators and communications equipment. Greater availability of such resources to remote communities would enhance their resilience in the face of a range of natural hazards.

Benefits of flood-resilient building design – Building designs which integrate water resistant materials such as concrete and cement and tiles in favour of soft timbers, carpets and gyprock walls, prove to be far more resilient to flooding.

Business resilience had been enhanced through elevated shelving and storage areas used for relocating stock during flooding. However, in the most severely impacted locations these measures were overwhelmed by the height of flood waters.

Limitations of house raising – This event has shown that house raising can afford people a false sense of security and result in people becoming trapped in extreme flood events. Although house raising may reduce frequent flood damage, there are clear public safety risks in areas where significant flood depths of several metres could occur. House raising on this basis should be evaluated and perhaps restricted in areas where significant flood depths could occur.

The following sections provide an overview of flood impacts across the different communities visited.

The Wilsons River and Richmond River catchments (including Leycester Creek)

Casino (Richmond River):

- Reports from shop owners in the city centre were that the CBD was inundated by between 40 – 60cm of water

- Some shop owners thought that widespread complacency among businesses (from many years without experiencing floods) had prevented many from making preparations such as moving stock. Businesses took well over a week to reopen as a result.

- Significant erosion of the rivers banks was evident, as was a destroyed roadway beneath the Irving Bridge (Figure 3).

- A businesswoman who owned multiple stores that had been flooded spoke of her surprise of the height of the peak flood levels. Being higher than expected meant that preparations proved insufficient.

- Between Casino and Lismore, there were numerous examples of infrastructure damage (from flood waters) and landslides from heavy rain (Figure 4). Some roads between the two towns were still closed to general traffic because of rockfalls and damage to roadways, causing detours to be put in place.

Lismore CBD (Wilsons River):

- The Lismore CBD was extensively impacted with examples of structural damage to: storm drains and gutters; stone and concrete walls adjacent to the river; and the rear of the Richmond Hotel, which had collapsed (Figure 5). Bitumen surfaces of car parks and roads had also been stripped away in multiple locations. There were also numerous examples of shops boarded up from broken shop windows and bent street signs. Businesses raised stock to levels above the 1974 flood level, to no avail.

- Flood water in the Lismore CBD exceeded 4 metres, completely inundating most residential and commercial buildings and reaching to the top of telephone poles and other major business signage (Figure 6).

- As at the 19th of March, virtually all businesses in the Lismore CBD remained closed (including McDonald’s). Notable exceptions were a hotel, which one of our researchers recalled also reopened directly after the 2001 flood, and a local car dealership.

- The car dealership, located in the CBD (in the vicinity of McDonald’s (Figure 6)), had also been totally inundated, but was able to reopen after only one week, by following their flood plan and evacuating early. The dealership owners have adopted a conservative approach to flooding which is reflected in the businesses flood plan. This included monitoring surrounding catchment rainfall totals, BoM warnings, and nearby creek levels and their personal experience with past flooding at the dealerships location. By the time the SES warning to evacuate the Lismore CBD was received at 2am on Monday 28th February, the business premises were already extensively flooded, though all the dealerships’ vehicles had been relocated and the office had been dismantled and moved by truck more than a day earlier.

South Lismore (Wilsons River):

- Many people in South Lismore made the decision to remain in their homes. The 2017 level had not risen to the second level of the ‘Queenslander’-style homes common in many areas of Lismore. Many residents went to bed on Sunday night (27th February), only to wake in the early hours of the morning to find water in their second-storey bedrooms. The flood peak reached 14.4 metres.

- People reported being forced to take refuge in their roof cavities, with the speed of rising water preventing them from exiting homes via windows and doors. There were also accounts of people dismantling roofs from inside to gain access to the roof to escape rising waters. Many people were forced to take refuge and await rescue by boat.

- Residents were critical of the lack of emergency resources to perform the number of rescues required in Lismore, highlighting the role of private citizens in saving numerous lives.

- Examples of structural damage to the exterior of homes and businesses in South Lismore ranged from cracked walls and masonry to partial or total building collapse (Figure 7).

- At Lismore Airport, at least eight planes were swept away and deposited in nearby paddocks. With limited warning, several other aircraft had been successfully relocated to the highest point in the airport and were saved as a result.

- A caravan park appeared completely abandoned after the large-scale dislodgement of every dwelling in the park. All cabins and caravans with fixed annexes were lifted off piers and smashed into those nearby, once again highlighting the vulnerability of caravan parks in low-lying areas to flooding. Most caravans had all, or part of their towing mechanisms removed, totally negating their mobility.

Coraki (Wilsons and Richmond Rivers):

- Extensive flooding was evident throughout the town, with water levels > 2 metres in lower lying residential areas.

- The local hotel, which had just undergone a major refurbishment, suffered significant damage. Water levels rose quickly to approximately 1 metre above the 1974 level (Figure 8) and inundated the entire ground floor and destroyed antiques and an entire kitchen of brand-new appliances before they could be relocated.

Woodburn (Richmond River):

- Woodburn, directly adjacent to the Richmond River, experienced significant water depths, > 3 metres (Figure 9) and > 4 metres in lower-lying areas.

- One clothing store owner reported that warnings of the oncoming flood came far too late and had severely underestimated both the peak level of flood waters and the speed with which the water rose. The owner reported hastily moving floor stock to a high mezzanine storage platform inside his shop, although this too was inundated, causing the loss of approximately $60,000 in clothing stock. There were also reports of looting occurring, with one offender being trapped by the speed of rising waters before apprehension.

- There was no evidence of any businesses open and trading in Woodburn, with all premises showing evidence of severe inundation. Power and NBN were only just being re-established

- Most residences in Woodburn appeared to have suffered major inundation, with clean-up of disposed possessions still occurring. Water levels in lower-lying residential areas exceeded 4 metres and reached the eaves of two-storey dwellings.

Broadwater (Richmond River):

- A number of residences in Broadwater appear to have suffered structural damage to walls and outside extensions. There were examples of large sand deposits left behind by floodwaters in front yards and along roadways seen through the town (Figure 10).

- The Broadwater Sugar Mill and Cape Byron Power Plant (occupying the same premises) were out of operation. Over 1.5 metres of water inundated the ground floor of the site which sits directly adjacent to the Richmond River. The mill and power plants are major employers in the area. Employees mentioned that operations could take months to resume.

- In some areas of Broadwater, flood heights exceeded 3 metres, with businesses remaining closed and premises showing the signs of significant inundation. There were also numerous examples of cars still lying on their sides and roofs among deposits of sand and other debris after more than two weeks (Figure 11).

- The vulnerability of caravan parks to flooding was again highlighted at the local park, where all dwellings had suffered severe inundation, some with structural damage.

Wardell (Richmond River):

- The Wardell CBD being directly adjacent to the flooding Richmond River resulted in mass inundation of all business and residences in the main street. Water level marks on walls and on those fences left standing indicated water heights of > 1 metre.

- Only one business, the post office and pharmacy (occupying the same premises), had resumed limited trading. Several other businesses were still cleaning premises in the hope of reopening once certified safe.

- There were numerous examples of fences flattened by fast-moving flood water which contained significant mud, grass and sugarcane debris which was swept into waters from paddocks. upstream. In the main street, an entire tree still lay where the flood had deposited it

Many flood-impacted people across the region had lost the important documentation useful in making claims for business grants and recovery assistance.

Ballina / West Ballina (Richmond River):

- Homes directly adjacent to the Richmond River showed signs of inundation, with water-damaged possessions on the footpath awaiting collection and clearly defined water level indicators on garden walls and garage doors of approximately 75cm.

- The Burns Point car ferry was still out of service (> two weeks later) following the flood. The ferry’s primary submarine cable snapped in the high flow, causing the ferry to be pushed high on its entry driveway, causing damage to its hull (Figure 12). The ferry operators had prevented the ferry from being totally swept away by chaining the ferry to large, fixed pilings on the West Ballina disembarkation point. The ferry was still several days from resuming operation, awaiting a new cable from Brisbane which had been delayed due to the Brisbane floods, leaving the residents of Burns Point the burden of a 28 km round trip to travel to Ballina.

- Several West Ballina caravan parks in low-lying areas exhibited signs of significant water inundation, with most caravans and semi-permanent dwellings now appearing uninhabited and abandoned.

- A key aspect of flooding mentioned by numerous people in Ballina was the large number of fish found dead and washed up on beaches and riverbanks which had drowned in the flush of fresh water coming from upstream.

The Tweed and Brunswick River catchments (including Marshalls Creek)

Murwillumbah CBD (Tweed River):

- The Murwillumbah CBD was flooded when the levee protecting the area was overtopped

- Many businesses had reopened within three weeks of the flood. However, most of these were smaller shops (bakeries, homewares) that appeared to have flood-resilient design features, including their choice of flooring (for example, tiles) and raised spaces for storing stock and equipment. In contrast, many larger chain outlets remained closed, bringing into question why bigger chain outlets did not organise resumption of operations sooner.

South Murwillumbah (Tweed River)

- Evidence of extensive flooding was observed including the industrial estate and residential areas with depths of multiple metres.

- Some businesses that had raised floors to mitigate flood risk also appeared to have been flooded, though several appeared to be open and trading.

- There was extensive damage exhibited at a local caravan park with vast piles of destroyed possessions on the front roadway awaiting collection and disposal. This park, like many caravan parks, occupies low lying – flood prone land where the limited mobility of caravans beneath permanent annexes and decking commonly contributes to severe damages occasioned by dwellings.

- South Murwillumbah provided the most notable example of the capacity of flood waters to transport plastic water tanks from farms and rural supply outlets and discard them across the landscape or beneath fixed objects, such as the railway bridge seen in Figure 14. There were numerous examples of destroyed water tanks lying in paddocks and along roadsides seen across the entire Northern Rivers region.

Billinudgel (Marshalls Creek):

- About half of businesses in town had reopened. Despite having reopened, most businesses were clearly still repairing or cleaning stock and equipment. Flood waters were reported to be lower than those of the 1974 flood.

- The benefits of flood-resilient design were illustrated by the local hotel which, due to regular flooding, had considered the risk of inundation in the design of fixtures and equipment. This included hardwood timber construction throughout, fridge motors located in the roof and relocating stock, including poker machines, to the top of the bar. The business was not insured but considered the costs of flooding within its business plan. Following the flood, the hotel was closed for only a day and a half, although its kitchen was out for seven days and the internet was still unavailable.

Main Arm and Upper Main Arm (Brunswick River):

- Main Arm Road – the main route from Mullumbimby and Main Arm – remained closed after a large section of the bridge was washed away (Figure 15). Main Arm was isolated for three days following the flood.

- Landslides – the Brunswick River catchment experienced numerous landslides. Some were even visible at long distances as scars on the surrounding hillsides – the result of a combination of the extreme rainfall, pre-saturated soils and steep terrain. Numerous local roads had been blocked as hillside debris collapsed onto road surfaces.

- In the neighbouring Wilsons Creek catchment (to the south), locals described large landslides, some still active with the sounds of cracking, being responsible for isolating properties which were being supplied with provisions by air drops (Figure 16).

- The many causeways on Main Arm Road showed examples of torn up bitumen, eroded banks and exposed tree roots where soil had been stripped away by the force of flows (Figure 17). The valley floor provided numerous examples of deep and fast flowing flood waters having deposited large amounts of sediment – from sand to cobbles – over riverbanks, floodplains and across paddocks, roads and the grounds of Main Arm Public School, which remained closed. In places, sediment was in excess of 50 cm deep (Figure 17).

- There were numerous examples of destroyed vehicles having been pushed off roads and into the bush near causeways along Main Arm Road.

- Local volunteers had set up a checkpoint at Kohinur Community Hall on Main Arm Road controlling access to Upper Main Arm and beyond in response to disaster tourists travelling through the area.

- Community volunteers coordinating the checkpoint reported that over 100 properties remained isolated in the upper valley by landslides or destroyed driveways. Food and supply drops were being made by air or on foot, with the help of the army.

South Golden Beach and Ocean Shores (Marshalls Creek):

- Extensive damage to residential areas was evident throughout both towns.

Mullumbimby (Brunswick River):

- Relatively shallow flooding was experienced throughout Mullumbimby. Damage occurred to the CBD and residential areas.

- Warnings in Mullumbimby were inhibited due to communication outages – meaning people stepped out of their beds and into floodwater. All but a handful of businesses had reopened three weeks later.

Click here to download a .pdf version of this briefing note.