Community insurance against climate change, wildfires in California, and the need for forward-looking wildfire loss modelling

While other nations have used insurance markets to address climate impacts, until recently that has not been the case in the United States. California is the first U.S. state to consider innovative ideas, insurance policies, and risk transfer mechanisms to address climate change. Insurance companies want to account for climate change in calculating wildfire coverage, but consumer watchdogs in California have worried that homeowners will end up with higher premiums. Legislators from fire-damaged districts have said they are open to change because their constituents are already losing coverage. In hard-hit Napa Valley, which has burned multiple times in the past decade, successful winemakers and longtime residents have been weighing their options to rebuild or move out entirely because they have not been able to get insurance or the insurance has been unaffordable.

California’s streak of wildfires created record liability for insurers. Insurance companies lost a total of $20 billion in 2017 and 2018, twice the industry’s profits since 1991. Insurers have been assuming that climate change is here to stay, and so they have been urging the state to allow them to factor in future flooding, mudslides, and forest fires into customer premiums. Otherwise, they said that they would just continue to drop more homeowners from coverage in a state where one out of three homes have been built in or near dense vegetation.

The state has spent more than $4.7 billion from its emergency fund from 2010 through 2019 to fight fires. For the past several years, Cal Fire, the state’s firefighting agency, has been exhausting its firefighting budget only months into the year, leaving little to pay for thinning California’s overgrown forests and helping rural communities protect their infrastructure and water supplies.

So far, California’s approach has been to stabilize the financial health of the state’s electric utilities by creating a $21 billion compensation fund to pay for fire victims’ claims, seeded with equal contributions from the companies and their customers. They are also mandating more safety oversight and a requirement that the three largest utilities invest a total of $5 billion to fireproof their equipment. Increasingly, those precautions have included preemptively cutting the power in high-risk areas during windy, red-flag conditions, a measure that is extremely unpopular with customers. The state’s (and nation’s) largest electric power company, Pacific Gas & Electric, has announced that it will spend $30 billion to bury power lines in areas that are most vulnerable to wildfires, but charging those costs to consumers would have to be approved by the state Public Utilities Commission.

California’s fires are disruptive long after they are put out, displacing homeowners and even entire communities for months or years. Even as the charred wood decays, it generates emissions that set back the state’s efforts to combat climate change, potentially intensifying the wildfires to come.

Protecting Communities, Preserving Nature, and Building Resiliency

With California communities facing increasing threats from increasing exposure to climate change, and unrest within the insurance industry, California Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara wrote the first climate insurance law in the United States to protect consumers in the years ahead. Senate Bill 30 (Chapter 614, Statutes of 2018) established a working group of environmental advocates, researchers, and insurance experts making recommendations for policies to reduce the costs from wildfires, extreme heat, and flooding, mudflows, urban high heat, and sea-level rise. On 22 July 2021 they released a report entitled “Protecting Communities, Preserving Nature, and Building Resiliency; How First-of-Its-Kind Climate Insurance Will Help Combat the Costs of Wildfires, Extreme Heat, and Floods.”

Among these recommendations was the consideration of parametric insurance policies – for all perils – to guarantee that all residents have some form of coverage. This should be supported by a pilot program that initiates a basic level of disaster insurance, and wider support and uptake of nature-based insurance solutions, such as coastal wetlands and floodplains to reduce flood losses and open space buffers to provide protection for wildfires.

Impact of Climate Change on Wildfire Occurrence

The role of climate change on wildfire occurrence, and impacts on insurance losses and affordability, is an active and complex area of research. Catastrophe loss (CAT) models are decision-support tools used widely in the (re)insurance industry to help price natural hazard risk and aggregate risk management. To a certain extent, the cost of insurance against extreme weather is dictated by the view of risk portrayed in these models.

Traditionally, CAT models provide a view of risk for the forthcoming financial year. However, of late, there has been more demand for CAT models to also take a forward-looking view of natural hazard risk and in doing so to incorporate the impacts of climate change on insured losses. Wildfire frequency and severity directly depends on a range of weather and environment variables such as temperature, humidity, soil moisture and the availability of fuel which are all linked to climate patterns.

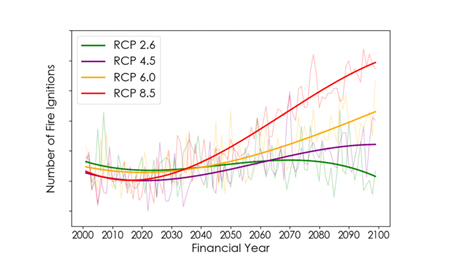

FireAUS is Risk Frontiers’ bush and grass fire catastrophe loss model for Australia. The hazard component of FireAUS includes an ignition model which uses nine weather variables, amongst other predictors. This model can be used to estimate the potential number of fire-starts for a given spatial and temporal region. Since the ignition model explicitly relies on weather variables that are also available through General Circulation Models (GCM), the same ignition model can be used to estimate the changes in fire ignition frequency for a given future emission scenario (Figure 2).

Risk Frontiers has recently embarked on a two-year research project to transfer knowledge from the development of FireAUS to North America. This is expected to bring a view of present and future wildfire risk in North America that integrates our unique blend of climate science, machine learning and remote sensing expertise. The shared wildfire experience in California and Australia – and the role of insurance in building resilience – highlights the potential for significant knowledge transfer in modelling the fire landscape in both these regions.

References

http://www.insurance.ca.gov/cci/docs/climate-insurance-report-07-22-2021.pdf

http://www.insurance.ca.gov/cci/docs/climate-report-2-page-summary.pdf

Click on the link below to download the pdf version of this briefing note.