A brief history of ransomware

Introduction

A ransomware is a malicious software introduced and run on a victim’s computer system to disrupt the availability of information in a controlled manner. Cyber criminals mainly use ransomware for two purposes: (a) to encrypt documents that are deemed important or valuable and (b) to prevent victims from accessing their information system. Either way, the attacker’s motive is to extort payments from their victims through threat of data loss or leak, denial of service and increased ransom demand.

Although the word ransomware has become common jargon, its history is quite interesting, full of opportunistic innovations and twists.

The birth of cryptovirus

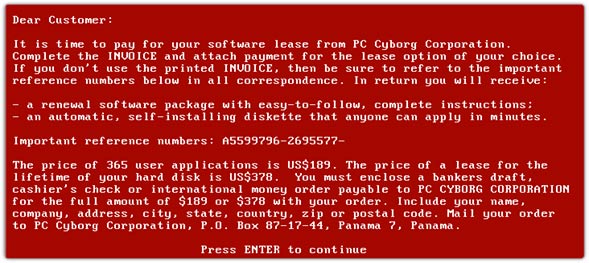

In 1989, Dr. Joseph Popp created and distributed the “AIDS Information Introductory Diskette”, a floppy disk that supposedly contained AIDS research information. About 20,000 copies of the disk were physically distributed to 90 countries using a mailing list composed of conference subscribers[1] – quite an expensive undertaking. Little did they know that the disk contained a trojan (a malware disguised as a legitimate software), known as the PC Cyborg Trojan or AIDS ransomware – the first ransomware or cryptovirus. When a victim loaded the disk on a computer, the trojan self-installed by replacing the autoexec.bat found in early versions of the Microsoft Windows Operating System. This compromised executable counts the number of times the computer was booted-up and, on the 90th iteration, the names of all files on the C: drive were encrypted. This malicious action prevented the OS from operating unless the filenames were restored. A “ransom note” was then displayed on the computer screen demanding the payment of up to $378 for “license renewal” (Figure 1).

Three important features of Popp’s ransomware are (1) the slow and expensive distribution method, (2) rudimentary use of encryption techniques[2] and (3) physically traceable ransom payments. It can be argued that the immaturity of the public internet in the 1980-90s militated against Popp’s plan. However, his concept was quite ingenious, though mischievous, and this technique was refined over the next decades. The PC Cyber Trojan set the scene for what would become one of the most lucrative businesses in the cybercrime ecosystem – digital extortion.

The rise of ransomware

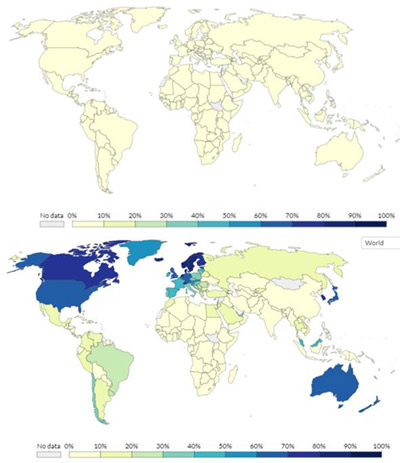

In the two decades following the introduction of the AIDS ransomware, the number of people using and relying on the Internet drastically increased, especially with the wide adoption of the World Wide Web. By 2005, more than 60% of the population in Australia, New Zealand, Japan, South Korea, North America and many European countries were regularly using the internet (Figure 2).

Many giants of the digital marketplace such as Amazon, Etsy and eBay were formed in the mid-1990s. By 2004, a considerable number of people and businesses relied on online payments, prompting the creation of the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI-DSS) to ensure the security of online payments and compliance of businesses processing them.

In 2004, ransomware attacks re-emerged, with GpCode and other similar families of trojans. With the established and worldwide adoption of email communication, the GpCode trojan was distributed through a spam campaign where victims were tricked into downloading a malicious Word .doc file masquerading as a job application form. The email addresses were harvested from a major Russian job recruitment website (job.ru) and the phishing emails duped the victims into believing that the job offer was legitimate. The attachment contained a macro that downloaded and installed a series of trojans and ended with a running GpCode malware on the victim’s computer. Once installed, GpCode encrypted more than 80 different file types (such as .doc, .pdf, .xls, .jpg, etc.).

GpCode is a considerable improvement over Dr Popp’s AIDS ransomware. Firstly, email distribution is much more efficient and scalable than mailing floppy disks or USBs. Scaffolding through multiple trojans to install the final payload and delayed encryption required careful planning as they made it difficult for the victims to link the infection to the recruitment emails. Secondly, the payments were to be sent to either of two digital currency services, e-gold and Liberty Reserve, both of which were payment systems favoured by criminals[3]. Thirdly, and most importantly, the encryption techniques and schemes changed rapidly over the lifetime of the GpCode Trojan, which shows the speed at which the ransomware improved[4]. The encryption technique evolved from home-brewed algorithms to more sophisticated cryptographic schemes using asymmetric cryptography. In fact, Young and Yung foresaw in 1996 that asymmetric cryptography can be effectively used by ransomwares as they would only store the public key (for encryption) in the malicious payload while the private key (for decryption) remained secret with the actors [1]. Indeed, later versions of GpCode leveraged RSA[5] and the following simplified scheme[6]:

- Create a unique machine key K for the infected computer

- For each targeted file:

Encrypt the file using K (and the associated encryption method) - Encrypt K with the included RSA public key and write the ciphertext in _READ_ME_!.txt

- Forget K.

If the files are encrypted using a strong scheme and a long key K, such as the Advanced Encryption Scheme (AES) with a 128-bit key, then the only way to get the files back is to send _READ_ME_!.txt to the ransomware operators (with the ransom payment) and receive the decrypted K (bundled as a decryption software kit).

All modern ransomware uses a variation of the scheme above as their core functionality. For instance, the key K is usually unique for each targeted file and the encrypted K is concatenated with the encrypted file.

A quest for the perfect coin

In 2008, “Satoshi Nakamoto” published the seminal paper that underpins the inner workings of the bitcoin network ━ a blockchain [2]. Simply put, Bitcoin is:

A purely peer-to-peer version of electronic cash [that] would allow online payments to be sent directly from one party to another without going through a financial institution.

The peer-to-peer approach allows two parties to directly conduct a mutual transaction without relying on a trusted third-party (e.g., banks) under the jurisdiction of state authorities. Technically, all transactions are stored as sequences of blocks, forming a distributed ledger. All parties participating in the bitcoin transactions or coin mining process agree that that ledger represents the current distribution of bitcoin wealth. This is referred to as consensus in blockchain lingo.

During its first year, bitcoin valuation was decided by the few contributing members, but wider adoption and speculation brought it to its current high valuation. Over time, it became the currency of choice for criminals. It is a payment system that suits ransomware well due to the following qualities:

- Fungible: bitcoin is currently the most widely cryptocurrency and that value is accepted and supported by its large user base

- Pseudo-anonymous[7]: no ID is required to create a bitcoin wallet; a must for cyber criminals.

- Immutable: once a ransom payment is executed (i.e., mined in a block), it cannot be reversed without the recipient’s private key, unlike a credit card transaction reversal by banks or gift card revocation by a retail store

- Decentralised: no single entity controls the blockchain network upon which Bitcoin lives. This means that it is extremely unlikely to be taken down by state authorities, unlike centralised digital payment services (e.g., e-gold and Liberty Reserve have ceased to operate)

- Automated: all aspects of the ransom payment can be automated, from bitcoin wallet creation to cashing out into fiat currency.

Then in 2013, the CryptoLocker trojan brought about various major improvements in the world of ransomware. Firstly, it used an existing cybercriminal infrastructure, the Gameover ZeuS botnet[8], in addition to more conventional spam campaigns for its distribution mechanism. This type of distribution was fully exploited by the ransomware gang behind Locky, three years later, to become the first verifiable multi-million dollar ransomware. Secondly, the CryptoLocker trojan uses 2048-bit RSA to encrypt the targeted files directly, making it impossible to crack without the private key. Each infected computer would contact one of many control servers to receive a unique public key. The associated private key remains on the server, which paved the way to an automated web-based decryption service upon ransom payment. Lastly, it leveraged the rising star of virtual currency which is a good fit for ransom payments (Figure 3). Although Bitcoin is not perfect (as we shall see later), it has come a long way since Popp’s bankers’ draft.

Another important feature of CryptoLocker is the infliction of psychological pressure on the victims[9]. The threat is reinforced with some sense of urgency using a countdown towards a ransom doubling or the destruction of the private key stored on the control servers. However, after the Gameover ZeuS botnet was taken down, salvaged private keys databases were used to create an online tool to recover the keys and files without ransom payment.

A profitable business

By 2016, organised cyber criminals like the ones behind the Locky ransomware were refining the art of digital extortion. All features of the CryptoLocker trojan are included in Locky. In particular, the Locky malware was distributed through spam campaigns leveraging the Necurs botnet to reach hundreds of millions of potential victims on a daily basis. The Locky gang leased existing infrastructure from other criminals, thus reinvigorating the now-complex economics of cybercrime. The Locky malware is downloaded by a malicious macro embedded in a word .doc file masquerading as an invoice or gibberish to deceive the victim into enabling the MS word macro[10]. Once the victim downloads and opens the attachment, the Locky malware is automatically downloaded and loaded into the computer’s memory[11]. It then starts encrypting files using a cryptographic scheme like that of GpCode but utilising RSA-2048 in conjunction with AES-128. The RSA public key is generated on the server side and sent to the infected computer via secure communication.

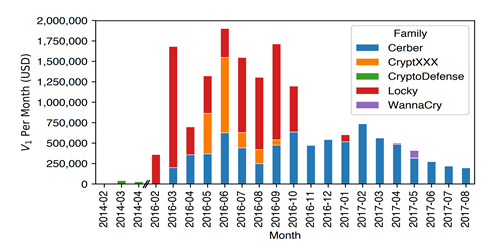

Since 2013, Bitcoin has become the currency of choice for ransomware, including Locky. Since the bitcoin ledger is public, researchers from Google, Chainalysis and a group of US-based universities tracked bitcoin ransom payments for various ransomware families [3][12]. Their findings revealed that ransomware alone is a multi-million dollar business. Figure 4 shows that Locky (and its variants) collected more than USD 7 million in ransom during its 8-month lifespan. The Cerber ransomware family received a similar amount but over a more sustained period of operation. Figure 4 would seem to indicate a decline in ransomware losses, but the researchers noted that figure is likely conservative due to technical limitations in the study. However, the bottom line is that ransomware is a lucrative business, as long as the victims are willing (or forced) to pay.

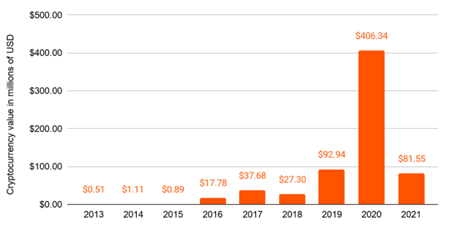

Fast forward to 2020, the total payment extorted by ransomware operators is estimated to be more than USD 400 million, held in various cryptocurrencies (Figure 5).

A serious threat

With its economic rise, ransomware has cemented its place in the cybercrime ecosystem. Ransomware actors often lease large botnet infrastructures to extend their reach and perform mass scans for potential vulnerabilities in publicly facing IT infrastructures. In addition, they consume exploit kits, stolen credentials and access to compromised systems sold by other cyber criminals. This allows ransomware operators to target larger organisations and specialised businesses. Thus, ransomware earnings are becoming a major source of revenue for the entire cyber black market.

The advent of Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) adds another layer of complexity and extra source of revenue for ransomware authors and operators. Ransomware trojans are bundled as a package that is available for purchase and use by individuals with extremely limited technical abilities. The bundle is accompanied with documentation, feature updates and even 24/7 technical support. More recently, RaaS is becoming a Software as a Service-like business model that anyone can subscribe to for a flat monthly fee, through affiliate programs (where the RaaS operators keep a percentage of the ransoms received in addition to the monthly fee), one-time license or full profit sharing (through partnerships).

Many technical improvements have been observed in recent ransomware core capabilities. They include in-place encryption (rendering specialised document recovery software useless), encryption-by-proxy or process injection (making it appear that the encryption of files is run by a trusted application), self-replication (worm-like capabilities such as WannaCry’s ability to automatically spread through a network using EternalBlue for access and DoublePulsar for replication), and many others[14]. However, it is clear that the emergence of RaaS is the new major addition that has pushed ransomware to the forefront of cybercrime. RaaS scales the threat actors themselves.

The most recent ransomware attacks[15] show the potential impact of this business model.

Kaseya attack July 2021

On July 2, businesses and governments around the world were scrambling to understand yet another major ransomware attack, which could potentially cost tens of millions of dollars and affect more than 1,000 other companies. The attack has been attributed by experts to the REvil ransomware (also known as Sodinokibi or Sodin). The REvil RaaS is developed and operated by the Pinchy Spider criminal group. The hackers hit a range of Managed Security Providers (MSP) and compromised their corporate clients through a supply chain attack using Kaseya’s Virtual System Administrator software. The attackers requested a $70 million payment in bitcoin in exchange for a universal decryption tool that could help victims recover from the attack.

JBS attack June 2021[16]

On June 3, the FBI attributed the ransomware attack on meat processing giant JBS to the REvil ransomware. JBS was specifically targeted, as reconnaissance started as early as February 2021 and analyses seem to indicate the primary group was involved rather than an affiliate. In early March, credentials belonging to JBS Australia employees were leaked on the dark web, which confirms a successful reconnaissance phase. Netflow analysis showed that excessive data extrafiltration occurred from March to May. Once the group got the data out, the Sodinokibi malware was used to encrypt the data on the system, which led to the operational disruption. On June 9, JBS paid USD 11 million in bitcoin to avoid further disruption.

Colonial Pipeline attack May 2021[17]

A DarkSide affiliate was identified by the FBI as the perpetrator of the Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack disclosed on May 7. The DarkSide RaaS is developed and operated by the Carbon Spider criminal group. The affiliate threat actors were able to extrafiltrate 100 GB of data from the Colonial IT systems before encryption with the DarkSide ransomware. The actors then threatened to leak the sensitive data through their Hall of Shame gallery in addition to the standard ransomware threat. This name-and-shame tactic has become a common trend amongst ransomware actors to increase the psychological pressure on the victims. Colonial has paid around USD 5 million (75 bitcoins at the time of payment).

These sequential attacks are enough to highlight the potentially devastating impact of RaaS on the economic and social life of a country and its critical infrastructure. They are also perfect examples of the indirect cost of ransomware attacks (such as business interruption). The May and June attacks have, in part, prompted the US president to publicly and actively condemn the actions of cyber criminals, and raise the issue with his Russian counterpart[18]. In fact, announcements regarding potential (cyber) military involvement and possible “repercussions, consequences and retaliation” were made by US government officials. Within the same week, it was confirmed that the majority of the ransom payment was recovered by law enforcement[19]. The recovery operation was not fully disclosed but the acquisition of a wallet’s private key by the FBI, where 63.7 of the 75 bitcoins were deposited, is an interesting detail.

Thwarting ransomware attacks

The recent attacks show that ransomware is clearly a major global issue and requires fighting on multiple fronts to oppose. Topics about ransomware are now banned (at least temporarily) on popular hacking forums, such as Exploit and XSS, used to recruit partners and affiliates. RaaS operators, such as those behind REvil, have also announced that they will change their operational codes of conduct (if there is any such thing) and will pre-approve affiliates’ target before any attack[20]. The tracking of bitcoin payments and involvement of law enforcement in the recovery of the Colonial Pipeline ransom are also important new developments which may help thwart and disincentivise ransomware activities. However, tangible impacts of these events remain to be seen. What is certain is that ransomwares and their operators will continue to evolve. All businesses should continue to proactively secure their IT systems and employees against this type of attack.

Human activities remain an important point of entry for ransomware through phishing and social engineering. This can either be through clicking a link, opening an attachment or installing some compromised application. This means that businesses should proactively ensure that employees are aware of potential entry points that ransomware operators actively exploit.

On a more technical side, Australian businesses should follow the Essential Eight suggested by the Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC)[21]. These include application control, regular patching (applications and operating systems), Microsoft Office macro settings, access controls, multi-factor authentication (especially for remote access) and regular backups. These mitigation strategies are important for good cyber hygiene and go a long way to prevent and limit the extent of a potential breach. However, it is also important to have a clear and rehearsed incident response plan, because well-resourced, motivated and skilled hackers will almost certainly compromise their targets. The ACSC also provides a detailed response guide for a ransomware attack[22].

Globally, governments are aware of the impacts of ransomware attacks, especially given their success over the past few years. One important case is the Colonial Pipeline attack, which highlights the fact that the impact of ransomware is not limited to businesses but can also affect critical infrastructures. For Australia, the protection of critical infrastructures is the first key theme in the Australian Cyber Security Strategy 2020[23]. More recent developments also show that governments should deter sophisticated cybercriminals. The high-profile meeting between the US and Russian presidents, or the creation of a Joint Cyber Unit to respond to large-scale cyber attacks on the EU and its Member States, are all positive steps towards thwarting ransomware attacks and cybercrimes in general. Indeed, deterrence strategies are important mitigation techniques for ransomware as their operators will continue to seek victims as long as these attacks are profitable.

Ransomware and cyber insurance

Cyber insurance is another component of cyber security risk management. As a risk transfer strategy, it is particularly useful as part of an incident response plan. Most stand-alone cyber insurance policies include incident response costs and, for ransomware attacks, they also cover ransom negotiation and payment. This is becoming a major challenge for insurers as ransomware operators do factor in the availability of information regarding the victim’s cyber insurance into their ransom pricing and negotiation. In 2020 alone, Lockton have observed that 15% of all notified claims were ransomware related but they accounted for 95% of the paid amounts[24]. Indeed, ransomware claims are now a major driver in cyber insurance losses[25] which impacts both availability and affordability as insurers try to balance limits and premium pricing, coverage demands, client selection and the evolving ransomware risk landscape[26].

References

[1] A. Young and Moti Yung. Cryptovirology: extortion-based security threats and countermeasures. IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy. 1996

[2] Satoshi Nakamoto. Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system. 2008

[3] Huang et al. Tracking desktop ransomware payments end-to-end. IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy. 2018

[1] The list contained subscribers to the World Health Organisation’s AIDS conference.

[2] In fact, symmetric cryptography was used by Popp in his trojan, which meant that the encryption key (which is the same as the decryption key) had to be stored in the payload. This made the code very easy to break.

[3] Later versions of GpCode used Yandex as well. E-gold and Liberty Reserve have since been taken down.

[4] https://securelist.com/blackmailer-the-story-of-gpcode/36089/

[5] The cryptosystem that underpins state-of-the-art secure communication.

[6] http://rump2008.cr.yp.to/6b53f0dad2c752ac2fd7cb80e8714a90.pdf

[7] Anonymity can potentially be broken once the coin “moves off the blockchain” and transforms into fiat currency. Physical identity can then be linked to the wallet by bitcoin exchange services.

[8] A botnet is a network of private computers infected with malicious software and controlled as a group without the owners’ knowledge, e.g., to send spam or mine for cryptocurrencies.

[9] Psychological pressure was extensively exploited by ransomwares that did not encrypt any data (e.g., WinLocker or the Reveton family of trojans). These lockers simply blocked the victims’ access to the computer and threatened to expose some made-up accusation about the victim (by impersonating law enforcement) unless a ransom payment was made.

[10] Many variants of the malware exist with slightly different delivery methods.

[11] This means the malware is file-less; that is, it loads itself directly into the machine memory and wipes any of its existence on disk. This makes it harder for traditional anti-virus software to detect and block.

[12] The technique of tracking bitcoin ransom payment is also an important tool for law enforcement to “follow the money”.

[13] https://blog.chainalysis.com/reports/ransomware-update-may-2021

[14] https://www.sophos.com/en-us/medialibrary/PDFs/technical-papers/sophoslabs-ransomware-behavior-report.pdf

[15] https://www.blackfog.com/the-state-of-ransomware-in-2021/

[16] https://securityscorecard.com/blog/jbs-ransomware-attack-started-in-march

[17] https://securityscorecard.com/blog/new-evidence-supports-assessment-that-darkside-likely-responsible-for-colonial-pipeline-ransomware-attack-others-targeted

[18] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-06-14/putin-biden-geneva-summit-g7-cyber-crime-jbs/100212880

[19] https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/department-justice-seizes-23-million-cryptocurrency-paid-ransomware-extortionists-darkside

[20] https://therecord.media/darkside-ransomware-gang-says-it-lost-control-of-its-servers-money-a-day-after-biden-threat/

[21] https://www.cyber.gov.au/acsc/view-all-content/publications/essential-eight-explained

[22] https://www.cyber.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-11/ACSC%20-%20Emergency-Response-Guide.pdf

[23] https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/cyber-security-subsite/files/cyber-security-strategy-2020.pdf

[24] https://global.lockton.com/gb/en/news-insights/increasingly-severe-ransomware-claims-impact-the-cyber-insurance-market

[25] http://thoughtleadership.aon.com/Documents/202006-us-cyber-market-update.pdf

[26] https://assets.ctfassets.net/vdinc3339dpx/6cSvo4e99aNoF4loGLBpj4/133d5fd46139121071817978dc04d2e0/Ransomware_Darwinian_Challenge_for_Cyber_Insurance_White_Paper.pdf

About the author/s

Tahiry is a Software Engineer with years of experience working with multiple operating systems, container technology, programming languages and various software stacks. Tahiry holds degrees in Mathematics and a PhD in Computer Science.