The Great Hawkesbury Flood Turns 150

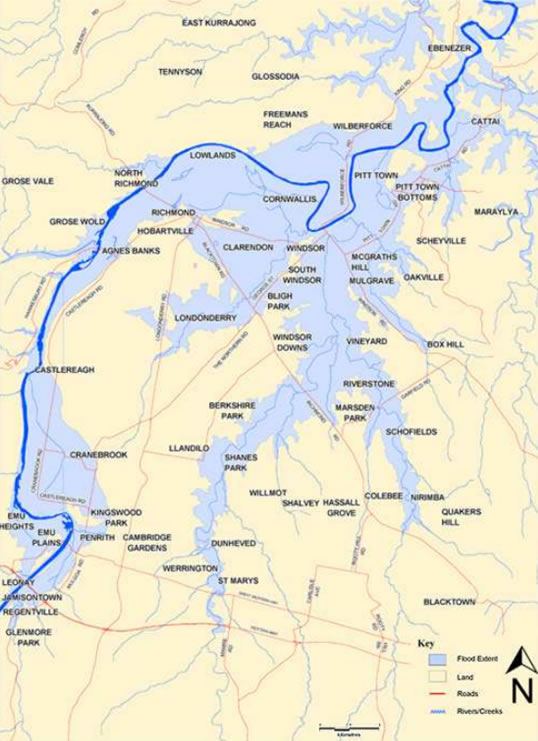

This week sees a significant but little-heralded anniversary in New South Wales: 150 years ago, on the 23rd of June, a devastating flood peaked at Windsor on the Hawkesbury River. For height reached and area inundated, that event has not been matched on the river since. Indeed no other flood since European settlement has come within 4 metres of that one at the Windsor gauge. The 1867 flood reached 19.7 metres: by comparison, the 1961 flood (the highest in living memory today) peaked at only 15.1 metres. The approximate extent of the 1867 flood is shown in Figure 1.

For context, the river in non-flood times reaches only about 1 metre at the gauge. So the 1867 flood peaked more than 18 metres above low-flow level.

Windsor became two small islands. Had the flood risen a further 3 metres, the town would have been completely inundated and many people would have been swept away.

Along the river, much of Windsor and Richmond and substantial tracts of farmland were flooded. Twelve people died, many dwellings were destroyed and hundreds of settlers made destitute.

Decades before, Governor Lachlan Macquarie had implored people to make their homes not on the river flats but on the high ground of the five ‘Macquarie towns’ he designated nearby. His advice was little heeded over following decades: people did not want to commute to their plots or have difficulty protecting their crops and livestock.

Unbeknownst to Macquarie, the town sites he had selected were within the reach of genuinely big floods. The 1867 flood proved as much.

Flooding not only impacted the Hawkesbury-Nepean catchment, but spread across NSW impacting other areas such as Parramatta, Liverpool, Bankstown, Wollongong, Nowra, Moruya, Tamworth, Bathurst, Mudgee, Dubbo, Forbes and Wagga Wagga. Such spread and intensity of impacts would no doubt stretch today’s emergency services (Yeo et al., 2017).

Over the following decades, population growth continued along the Hawkesbury, the area eventually becoming part of Sydney’s sprawl. Many houses were built within reach of much less severe floods than the 1867 event: McGraths Hill is a case in point. Even more dwellings were not far above the ‘shoreline’ of that event.

Here it must be appreciated that the highest flood possible at Windsor is estimated likely to reach to about 26 metres on the local gauge. All of Windsor would be inundated well before this level was reached. The islands of 1867 would disappear.

Such a big flood would occur only very rarely, but something like the flood of 1867 or higher must be expected at some stage. Adding height to Warragamba Dam as is proposed will not eliminate this potential.

By the late 1990s it was clear that the roads by which people evacuate would be cut by floodwaters well before a genuinely big flood reached its peak. All means of escape by road would be lost in a flood reaching a gauge height of only 14 metres at Windsor, with many thousands of residents cut off and at risk should the event develop into megaflood proportions as in 1867.

It would be utterly impossible to rescue all the trapped people by boat or helicopter. The death toll in a really big flood could be huge.

The state government’s strategy to avoid such an outcome was to build a high bridge between Windsor and Mulgrave. That structure was completed in 2007 at a cost of $120 million, its deck at a level equivalent to 17 metres at the Windsor gauge.

The bridge was intended to make it possible to get the potentially trapped people of Windsor and surrounding areas ─ 90,000 of them today ─ to safety in the face of severe flooding. It does not fully ‘solve’ the problem, though: inevitably, some people will not accept the recommendation to evacuate.

This reluctance to evacuate happens in every serious flood. Lismore, in late March 2017, was just the latest manifestation of this worrying response to flood in Australia. Scores of people ignored the warnings, failed to evacuate and had to be rescued. People underestimate the flood danger and put their own safety and that of emergency responders at risk.

This is the equivalent of the early settlers’ refusal to move their homes off the lower floodplain of the Hawkesbury.

The Windsor-Mulgrave bridge represents a belatedly learned lesson of the 1867 flood. The necessity for it grew from decades of residential development that ignored the reality of big floods. The other lesson, still not well appreciated despite many big floods, is that people should avoid being in the path of a severe flood. They need to understand, on the infrequent occasions when one of those is developing, that they should evacuate; otherwise, there is a real likelihood of deaths to themselves, families and friends.

The NSW Government has recently completed a review of Hawkesbury-Nepean flood management and has released a new Hawkesbury-Nepean Flood Risk Management Strategy entitled “Resilient Valley, Resilient Communities”. The strategy outlines key outcomes including raising the Warragamba Dam wall; preparation of a Regional Evacuation Road Master Plan and a Regional Land Use Planning Framework; raising community flood awareness; improving flood predictions; upgrading local evacuation routes and maintaining emergency plans. Continued Government support to ensure prudent management of current and future flood risk throughout the catchment is of upmost importance. The strategy can be downloaded at www.infrastructure.nsw.gov.au/expert-advice/hawkesbury-nepean-flood-risk-management-strategy.aspx.

Chas Keys is a former Deputy Director General of the NSW State Emergency Service and an Honorary Associate of Risk Frontiers at Macquarie University. For more information please contact Chas at chas.keys@keypoint.com.au or Andrew Gissing at andrew.gissing@riskfrontiers.com.

References YEO, S., BEWSHER, D., ROBINSON, J. & CINQUE, P. 2017. The June 1867 floods in NSW: causes, characteristics, impacts and lessons. Floodplain Management Australia National Conference. Newcastle, NSW.