The 14 August 2021 Mw 7.2 Haiti Earthquake and Multi-Source Compound Disasters

- BRIEFING NOTE 451

Introduction

Throughout its history, Haiti has been severely impacted by both earthquakes and hurricanes. Approaching tropical storm Grace threatens to drench Haiti by heavy rains, hindering response and recovery efforts in the aftermath of the 14 August 2021 Mw 7.2 Haiti earthquake by triggering landslides. Roads already made impassable by the earthquake could be further damaged by the rains, so aid teams are racing to get essential provisions to the affected region before Grace arrives.

As if an earthquake and hurricane was not bad enough, the recent assassination of Haiti’s President Jovenel Moïse in the capital, Port-au-Prince, on 7 July, and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has led to civil unrest and severely hindered disaster preparedness and response.

Unfortunately for Haitians, their country is a melting pot for compound disasters. The recent IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, released last week, highlights the potential for increasing compound extreme weather events in a warming world. However, this very recent real-world example reminds us that both seismic and human hazards can intersect with weather-related hazards, leading to devastating compound disasters situations.

Why so soon after the 2010 Mw 7.0 Haiti Earthquake?

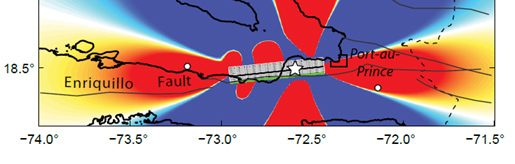

The previous large Haiti earthquake of 10 January 2010 occurred along the boundary of the North American Plate to the north and the Caribbean plate to the south, with the Caribbean plate moving east in relation to the North American plate (Figure 2). The motion between the Caribbean and North America plates is partitioned between two major east-west-trending, strike slip fault systems—the Septentrional fault system in northern Haiti and the Enriquillo-Plantain Garden fault zone (“Enriquillo fault”) in southern Haiti. The strain builds up with no motion on the fault until it exceeds the strength of the fault, generating sudden slip that causes an earthquake on the fault.

The Enriquillo fault has produced a series of major earthquakes in both instrumental and historical time periods. In addition to the 2021 Mw 7.2 earthquake and the 2010 Mw 7 earthquake (Eberhard et al., 2010) that devastated Port-au-Prince, the Enriquillo fault is the likely source of historical large earthquakes in 1860, 1770, and 1751. On October 18, 1751, a major earthquake caused heavy destruction in the Gulf of Azua at the eastern end of the Enriquillo fault. On November 21, 1751, a major earthquake destroyed Port-au-Prince but was centered to the east of the city on the Plaine du Cul-de-Sac. On June 3, 1770, a major earthquake destroyed Port-au-Prince again and appeared to be centered west of the city. As a result of the 1751 and 1770 earthquakes, local authorities required building with wood and forbade building with masonry. The resulting deforestation of the rugged hillsides had the compounding effect of allowing flood waters to rampage into large areas of the country during hurricanes, as described further below. The requirement of wood construct has evidently since been relaxed, given that much of the damage shown in media photos is to unreinforced masonry buildings.

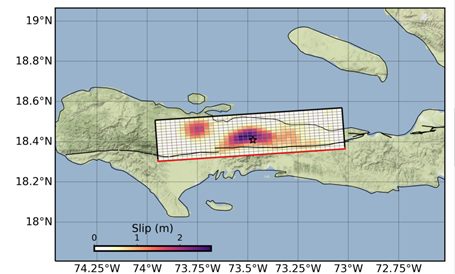

The 2021 Mw 7.2 earthquake (Figure 3) ruptured a segment of the Enriquillo fault that adjoins the west end of the fault segment that ruptured in 2010. Using calculated static stress changes on faults surrounding the January 12, 2010 earthquake on the Enriquillo Fault, and the first two weeks of the aftershock sequence, Lin et al. (2010) made rough estimates of the chance of a magnitude Mw ≥7 earthquake occurring during January 27 to February 22, 2010, in Haiti (Figure 4). The probability of such an event occurring to the west of the January 12, 2010 rupture in the ensuing month was estimated to be about one percent. The calculated static stress change was quite small, and the earthquake did not occur within the predicted one-month time frame, but it did occur in the 14 August 2021 event. It seems likely that stress transfer from the 2010 earthquake triggered the 2021 earthquake, but more rigorous methods than Coulomb static stress, involving dynamic stress modeling, would be required to accurately predict the timing of the event.

Relevance of stress transfer to Australia and New Zealand

Stress transfer is most likely to occur near plate boundaries. It may have been involved in the earthquake sequence along the northeast coast of the South Island of New Zealand involving the 2010 Mw 7.1 Christchurch and 2016 Mw 7.8 Kaikoura earthquakes (Risk Frontiers, 2016). Moreover, it may increase the likelihood of future earthquakes on shallow crustal faults such as the Wellington and Wairarapa faults and on the Hikurangi Subduction zone in the Wellington region (Risk Frontiers, 2018). In Australia, most historical earthquakes have not occurred on faults that have already been identified, so stress transfer may be less relevant to seismic hazard and risk assessment in Australia.

Casualties from Haiti earthquakes

The current estimate of deaths caused by the 2021 earthquake, which occurred in a region that is much less populated than Port-au-Prince, is approximately 1,400 people, with an estimated 6.900 injured, 37,000 houses damaged, and unknown numbers of unsheltered and missing people.

The 2010 Haiti earthquake caused major damage in the city of Port-au-Prince and the surrounding regions. On the first anniversary of that earthquake, 12 January 2011, Haitian Prime Minister Jean-Max Bellerive said that the death toll from the quake was more than 316,000. Several experts have questioned the validity of these death toll numbers. Edmond Mulet, UN Assistant Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations, said he did not think we will ever know what the death toll was from this earthquake, while the director of the Haitian Red Cross, Jean-Pierre Guiteau, noted that his organization had not had the time to count bodies, as their focus had been on the treatment of survivors.

Kolbe et al. (2010) generated a rapid assessment of the primary consequences for the population of the metropolitan area of Port-au-Prince, the national capital. They estimated that 158,679 people in Port-au-Prince died during the earthquake or in the six-week period afterwards owing to injuries or illness. Children were at particular risk for death. Of all households, 18.6 per cent were experiencing severe food insecurity six weeks after the earthquake. 24.4 per cent of respondents’ homes were completely destroyed. The earthquake led to the outbreak of a cholera epidemic outside of Port-au-Prince in October 2010 that caused over 820,000 cases and nearly 10,000 deaths: one of the worst cholera outbreaks in recent history. The frequently quoted estimate of 200,000 people for the overall death toll of the 2010 Haiti earthquake appears to be realistic.

Compounding impact of COVID-19 in Haiti

In March 2020, Haiti confirmed its first COVID-19 case and, a month later, confirmed its first COVID death, but did not receive any vaccine until July 2021. It is estimated that it currently has had over 20,000 cases and 576 deaths, which are impressively low figures. However, the coming hurricane season and the shortage of housing caused by the earthquake may exacerbate the impact of COVID-19 on Haiti.

Compounding impacts of hurricanes in Haiti

Haiti is expected to be drenched by heavy rains in the next few days as tropical storm Grace approaches, which may impede earthquake rescue and recovery work. Haiti is frequently impacted by hurricanes. In August 2020, Hurricane Laura, a Category 4 storm, killed at least 20 people in Haiti and knocked out power for more than a million people. In October 2016, Hurricane Matthew hit Haiti as a Category 4 storm, causing billions of dollars of damage, killing over 500 people, displacing thousands and devastating infrastructure. In October 2012, Hurricane Sandy was the cause of at least 51 deaths when it hit the country as a Category 2 storm. About 200,000 people became homeless after days of relentless rains.

The hurricane season of 2008 was one of the most severe ever experienced in Haiti. Four storms – Fay, Gustav, Hanna and Ike – dumped heavy rains on the impoverished nation. The rugged hillsides, stripped bare of 98% of their forest cover due to deforestation, let flood waters rampage into large areas of the country. These four storms killed 793, left 310 missing, injured 593, destroyed 22,702 homes and damaged another 84,625. About 800,000 people were affected – 8% of Haiti’s total population. The flood wiped out 70% of Haiti’s crops, resulting in dozens of deaths of children due to malnutrition in the months following the storms. Damage was estimated at over $1 billion, the costliest natural disaster in Haitian history. The damage amounted to over 5% of the country’s $17 billion GDP, a staggering blow for such a poor nation.

Summary

Historically, as a result of the 1751 and 1770 earthquakes, local authorities required building with wood and forbade building with masonry because of its collapse hazard. The resulting deforestation of the rugged hillsides had the compounding effect of allowing flood waters to rampage into large areas of the country during hurricanes. The requirement of wood construction has evidently since been relaxed, given that much of the earthquake damage in the 2010 and 2021 Haiti earthquakes has been to unreinforced masonry buildings.

Approaching tropical storm Grace threatens to drenched Haiti by heavy rains, hindering response and recovery efforts in the aftermath of the 14 August 2021 Mw 7.2 Haiti earthquake by triggering landslides. Roads already made impassable by the earthquake could be further damaged by the rains, so aid teams are racing to get essential provisions to the affected region before Grace arrives.

Unfortunately, Haiti – the poorest nation in the Western Hemisphere – is a real-world example of how extreme weather, earthquakes and human disasters can converge to amplify cumulative impacts. For those responsible for disaster risk reduction, it serves as yet another reminder of the importance of worst-case compound scenario planning across a range of hazards, and the pressing need for disaster finance to reach where it is most needed.

References

Eberhard, Marc O., Steven Baldridge, Justin Marshall, Walter Mooney, and Glenn J. Rix (2010). The MW 7.0 Haiti Earthquake of January 12, 2010. USGS/EERI Advance Reconnaissance Team Report. https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2010/1048/of2010-1048.pdf

Harris, Richard (2010). The Anatomy of a Caribbean Earthquake. https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=122531261

Kolbe, Athena R., Royce A. Hutson, Harry Shannon, Eileen Trzcinski, Bart Miles, Naomi Levitz, Marie Puccio, Leah James, Jean Roger Noel & Robert Muggah (2010). Mortality, crime and access to basic needs before and after the Haiti earthquake: a random survey of Port-au-Prince households, Medicine, Conflict and Survival, 26:4, 281-297, DOI: 10.1080/13623699.2010.535279

Lin, J., R. Stein, V. Seviglen, and S. Toda (2010). Coulomb stress-transfer model for the January 12, 2010 Mw 7.0 Haiti earthquake. USGS Open File Report 2010-1019.

Risk Frontiers (2016). The Mw 7.8 November 14, 2016 Kaikoura Earthquake, Briefing 3. RF Briefing Note 332.

Risk Frontiers (2018). Updated GNS Central New Zealand Earthquake Forecast, RF Briefing Note 364.

USGS (2021). M 7.2 Nippes, Haiti earthquake of 2021-08-14. https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us6000f65h/executive

About the author/s

Paul Somerville

Paul is Chief Geoscientist at Risk Frontiers. He has a PhD in Geophysics, and has 45 years experience as an engineering seismologist, including 15 years with Risk Frontiers. He has had first hand experience of damaging earthquakes in California, Japan, Taiwan and New Zealand. He works on the development of QuakeAUS and QuakeNZ.