Scars left by Australia’s undersea landslides reveal future tsunami potential

The following article, written by Tom Hubble and Samantha Clarke (U. Sydney) and Hannah Power and Kaya Wilson (U. Newcastle), appeared on The Conversation on December 10, 2017. The authors have modelled tsunamis that would be generated by these slides and conclude that “we suspect that such tsunamis pose little to no immediate threat to the coastal communities of eastern Australia” although it seems that very localised effects could be significant. Notably the article does not mention onshore geological evidence for the occurrence of large tsunamis in Australia (e.g. Bryant and Nott, 2001, attributed to cosmogenic sources by Bryant et al. 2007), perhaps because this evidence is highly controversial. There are few data on the speed with which these submarine landslides move; if they move slowly they may not be tsunamigenic.

One recent example of a destructive tsunami that may have been caused by an undersea landslide triggered by an earthquake is the 1998 Sissano Lagoon, New Guinea tsunami associated with an Mw 7.0 earthquake (Tappin et al., 2008; 2014). There is evidence that a delayed, earthquake-triggered, submarine slump caused 2200 deaths from a tsunami with maximum coastal flow depths of 16 m, and a focused runup along a limited length of coast. (I was a high school teacher for two years in Wewak, just down the coast from this event, and was motivated to study seismology after experiencing, some years earlier, a neighbouring earthquake that did not generate a tsunami).

It is often said that we know more about the surface of other planets than we do about our own deep ocean. To overcome this problem, we embarked on a voyage on CSIRO’s research vessel, the Southern Surveyor, to help map Australia’s continental slope – the region of seafloor connecting the shallow continental shelf to the deep oceanic abyssal plain.

The majority of our seafloor maps depict most of the ocean as blank and featureless (and the majority still do!). These maps are derived from wide-scale satellite data, which produce images showing only very large features such as sub-oceanic mountain ranges (like those seen on Google Earth). Compare that with the resolution of land-based imagery, which allows you to zoom in on individual trees in your own neighbourhood if you want to. But using a state-of-the art sonar system attached to the Southern Surveyor, we have now studied sections of the seafloor in more detail. In the process, we found evidence of huge underwater landslides close to shore over the past 25,000 years. Generally triggered by earthquakes, landslides like these can cause tsunamis.

Into the void

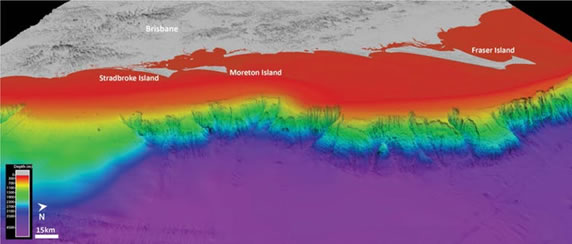

For 90% of the ocean, we still struggle to identify any feature the size of, say, Canberra. For this reason, we know more about the surface of Venus than we do about our own ocean’s depths. As we sailed the Southern Surveyor in 2013, a multibeam sonar system attached to the vessel revealed images of the ocean floor in unprecedented detail. Only 40-60km offshore from major cities including Sydney, Wollongong, Byron Bay and Brisbane, we found huge scars where sediment had collapsed, forming submarine landslides up to several tens of kilometres across.

What are submarine landslides?

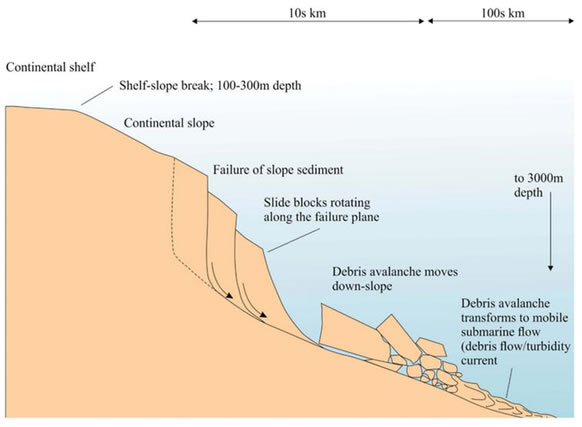

Submarine landslides, as the name suggests, are underwater landslides where seafloor sediments or rocks move down a slope towards the deep seafloor. They are caused by a variety of different triggers, including earthquakes and volcanic activity.

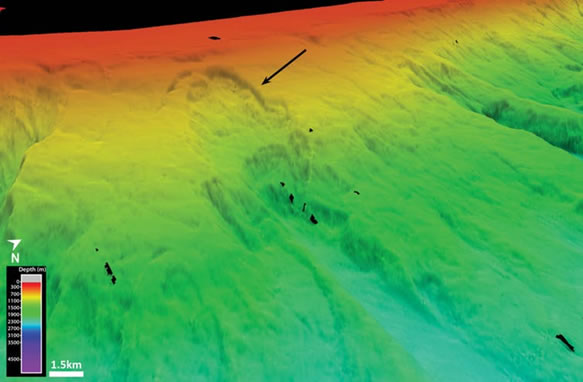

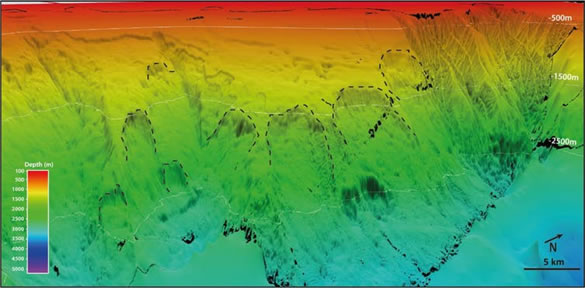

As we processed the incoming data to our vessel, images of the seafloor started to become clear. What we discovered was that an extensive region of the seafloor offshore New South Wales and Southern Queensland had experienced intense submarine landsliding over the past 15 million years. From these new, high-resolution images, we were able to identify over 250 individual historic submarine landslide scars, a number of which had the potential to generate a tsunami. The Byron Slide in the image below is a good example of one of the “smaller” submarine landslides we found – at 5.6km long, 3.5km wide, 220m thick and 1.5 cubic km in volume. This is equivalent to almost 1,000 Melbourne Cricket Grounds.

The historic slides we found range in size from less than 0.5 cubic km to more than 20 cubic km – the same as roughly 300 to 12,000 Melbourne Cricket Grounds. The slides travelled down slopes that were less than 6° on average (a 10% gradient), which is low in comparison to slides on land, which usually fail on slopes steeper than 11°.

We found several sites with cracks in the seafloor slope, suggesting that these regions may be unstable and ready to slide in the future. However, it is likely that these submarine landslides occur sporadically over geological timescales, which are much longer than a human lifetime. At a given site, landslides might happen once every 10,000 years, or even less frequently than this.

Since returning home, our investigations have focused on how, when, and why these submarine landslides occur. We found that east Australia’s submarine landslides are unexpectedly recent, at less than 25,000 years old, and relatively frequent in geological terms. We also found that for a submarine landslide to generate along east Australia today, it is highly likely that an external trigger is needed, such as an earthquake of magnitude 7 or greater. The generation of submarine landslides is associated with earthquakes from other places in the world.

Submarine landslides can lead to tsunamis ranging from small to catastrophic. For example, the 2011 Tohoku tsunami resulted in more than 16,000 individuals dead or missing, and is suggested to be caused by the combination of an earthquake and a submarine landslide that was triggered by an earthquake. Luckily, Australia experiences few large earthquakes, compared with places such as New Zealand and Peru.

Why should we care about submarine landslides?

We are concerned about the hazard we would face if a submarine landslide were to occur in the future, so we model what would happen in likely locations. Modelling is our best prediction method and requires combining seafloor maps and sediment data in computer models to work out how likely and dangerous a landslide threat is.

Our current models of tsunamis generated by submarine landslides suggest that some sites could represent a future tsunami risk for Australia’s east coast. We are currently investigating exactly what this threat might be, but we suspect that such tsunamis pose little to no immediate threat to the coastal communities of eastern Australia. That said, submarine landslides are an ongoing, widespread process on the east Australian continental slope, so the risk cannot be ignored (by scientists, at least). Of course it is hard to predict exactly when, where and how these submarine landslides will happen in future. Understanding past and potential slides, as well as improving the hazard and risk evaluation posed by any resulting tsunamis, is an important and ongoing task. In Australia, more than 85% of us live within 50km of the coast. Knowing what is happening far beneath the waves is a logical next step in the journey of scientific discovery.

References

Bryant, E.A. and J. Nott (2001). Geological indicators of large tsunami in Australia. Natural Hazards, 24, 231–249.

Bryant, E.A., G. Walsh and D. Abbott (2007). Cosmogenic mega-tsunami in the Australia region: are they supported by Aboriginal and Maori legends? University of Wollongong, Research Online

Tappin, D., P. Watts, and S.T, Grilli, (2008). The Papua New Guinea tsunami of 1998: anatomy of a catastrophic event. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 8, 243–266.

Tappin, D. et al. (2014). Did a submarine landslide contribute to the 2011 Tohoku tsunami? Marine Geology 357 (2014) 344-361.

About the author/s

Paul Somerville

Paul is Chief Geoscientist at Risk Frontiers. He has a PhD in Geophysics, and has 45 years experience as an engineering seismologist, including 15 years with Risk Frontiers. He has had first hand experience of damaging earthquakes in California, Japan, Taiwan and New Zealand. He works on the development of QuakeAUS and QuakeNZ.