Newton did OK working from home during a pandemic

Ben Cohen, author of the book “The Hot Hand: The Mystery and Science of Streaks” described “How the plague ravaged William Shakespeare’s world and inspired his work.” The plague closed London’s playhouses and forced Shakespeare’s acting company, the King’s Men, to get creative about performances. As they travelled the English countryside, stopping in rural towns that had not been stricken by the plague, Shakespeare felt that writing was a better use of his time. From the beginning of 1605 to the end of 1606, Shakespeare is thought to have written King Lear, Macbeth, and Antony and Cleopatra. Shakespeare also benefited from the plague because the plague killed off his competition. The King’s Men would eventually take back their indoor theatre spaces because of this disease that preyed on the young.

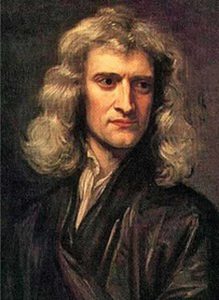

Gillian Brockell in The Washington Post, 13 March 2020, wrote the following article about Isaac Newton’s experience sixty years later in 1665:

During a pandemic, Isaac Newton had to work from home, too. It was time well spent.

Isaac Newton was in his early 20’s when the Great Plague of London hit. He wasn’t a “Sir” yet, didn’t have that big, formal wig. He was just another college student at Trinity College, Cambridge. Cambridge sent students home to continue their studies. For Newton, that meant Woolsthorpe Manor, the family estate about 100 kilometre north-west of Cambridge.

Without his professors to guide him, Newton apparently thrived. The year-plus he spent away was later referred to as his annus mirabilis, the “year of wonders.” First, he continued to work on mathematical problems he had begun at Cambridge; the papers he wrote on this became early calculus.

Next, he acquired a few prisms and experimented with them in his bedroom, even going so far as to bore a hole in his shutters so only a small beam could come through. From this sprung his theories on optics. And right outside his window at Woolsthorpe, there was an apple tree. That apple tree.

The story of how Newton sat under the tree, was bonked on the head by an apple and suddenly understood theories of gravity and motion, is largely apocryphal. But according to his assistant, John Conduitt, there’s an element of truth. Here’s how Conduitt later explained it: ” . . . Whilst he was musing in a garden it came into his thought that the same power of gravity (which made an apple fall from the tree to the ground) was not limited to a certain distance from the earth but must extend much farther than was usually thought. ‘Why not as high as the Moon?’ said he to himself..”

In London, a quarter of the population would die of plague from 1665 to 1666. It was one of the last major outbreaks in the 400 years that the Black Death ravaged Europe. Newton returned to Cambridge in 1667, theories in hand. Within six months, he was made a fellow; two years later, a professor.

So if you’re working or studying from home over the next few weeks, perhaps remember the example Newton set. Having time to muse and experiment in unstructured comfort proved life-changing for him – and no one remembers whether he made it out of his pyjamas before noon.

About the author/s

Paul Somerville

Paul is Chief Geoscientist at Risk Frontiers. He has a PhD in Geophysics, and has 45 years experience as an engineering seismologist, including 15 years with Risk Frontiers. He has had first hand experience of damaging earthquakes in California, Japan, Taiwan and New Zealand. He works on the development of QuakeAUS and QuakeNZ.