A flood of rain events: how does it stack up with the previous decade?

Lucinda Coates, Risk Frontiers

Some 40 people have died (including 3 missing presumed dead (mpd)) over the latest La Niña period (from November 2021 to the present) from floods across south-east Queensland (QLD), northern New South Wales (NSW), Greater Sydney and Victoria (VIC). In addition, there have been numerous instances of near misses and dramatic rescues.

During La Niña episodes, interactions between ocean and atmosphere act to increase the chance of rain to northern and eastern Australia. The tail end of the previous, 2020-21, La Niña episode (March 2021) brought extreme rain events and associated flooding to the eastern coastal regions and resulted in 3 deaths in NSW and 1 in QLD, as well as many near misses and rescues.

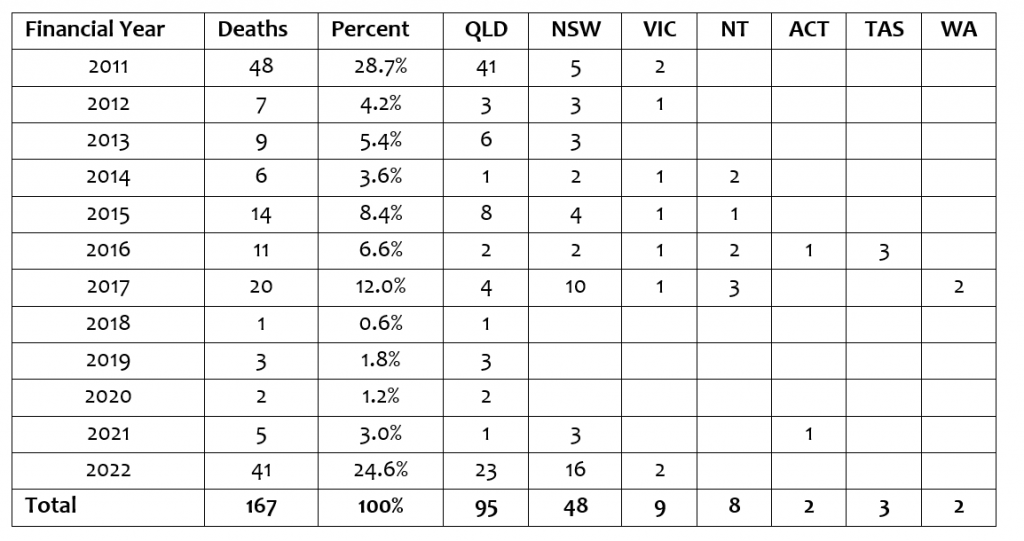

A previous series of consecutive La Niña episodes, 2010-11 and 2011-12, witnessed very heavy rain, especially in Queensland, over 2010-11. A total of 48 flood deaths occurred from August 2010 to June 2011: 3 in Victoria (VIC), 4 in NSW and 41 in QLD, including 17 deaths in the Lockyer Valley region alone on 10 January 2011 due to a flash flooding event.

In this current La Niña episode, the floods of November-December 2021 saw 1 death in VIC, 1 in NSW and 4 in QLD, while January 2022 saw 3 deaths (incl. 1 mpd) in QLD. In the February-April 2022 floods, there have been a total of 31 deaths: 16 deaths (incl. 1 mpd) in QLD, 14 (incl. 1 mpd) in NSW and 1 in VIC.

In relation to the Nov 2021-Apr 2022 La Niña period, the ages have ranged from 10-14 to 80-84, with the most deaths occurring in the 50-54 age group (n=7; 18%). A total of 28 males (70%) and 12 females (30%) died.

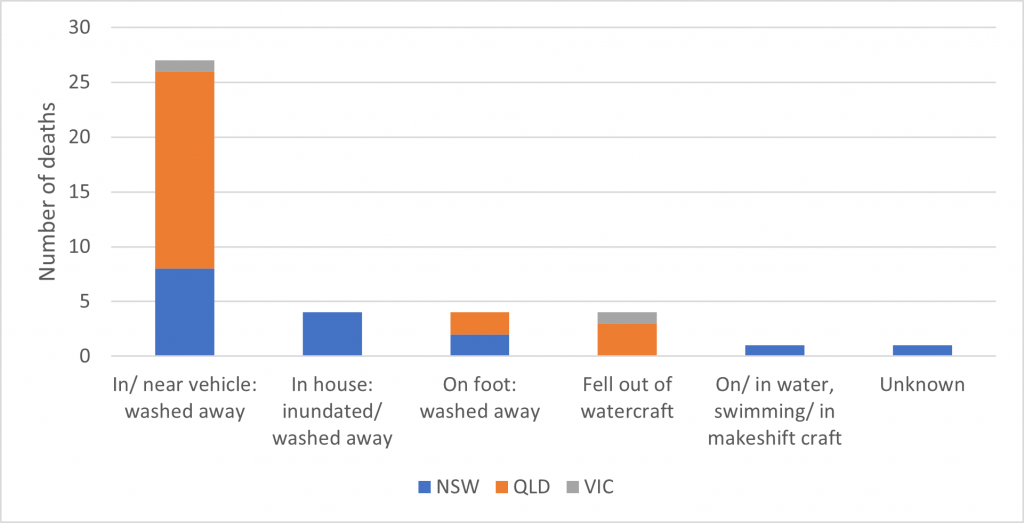

Two-thirds of the deaths (68%; n=27) were due to cars driving through and/ or being engulfed by floodwaters (Figure 1). All of the victims who were in a house that was engulfed by floodwaters or mudslides (10%; n=4) occurred in the Northern Rivers region of NSW in Feb-Mar 2022.

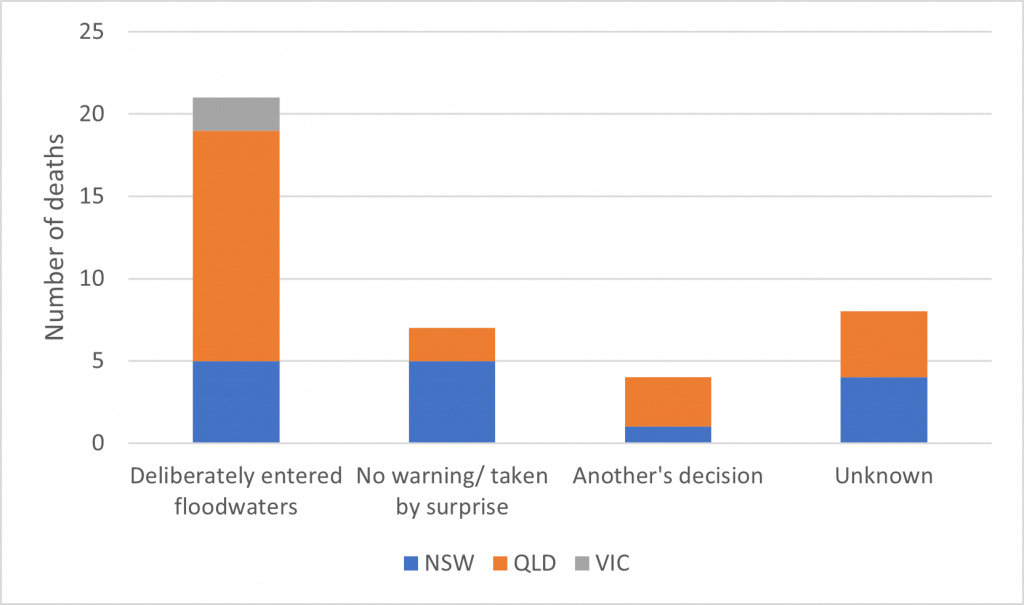

In most cases, the reason for the activity at the time of death was known (Figure 2) but for some it was not – e.g., of the 27 who died due to their car being washed away by floodwaters (Figure 1), 16 entered the floodwaters deliberately, 3 were taken by surprise (by a sudden “wave” of floodwater), 4 were passengers (therefore, it was another’s decision; this decision was to deliberately enter floodwaters in at least 3 cases) and this data was unknown for another 4.

PerilAUS, Risk Frontiers’ database of natural hazard occurrences and impacts in Australia, has data on the circumstances surrounding fatalities, sourced from news media articles, publicly available coronial records and various government enquiries and reports. PerilAUS was interrogated for flood deaths occurring since the 2011 financial year (FY): i.e., 1 July 2010-30 June 2011. In most of the charts below, the data set has been divided into deaths from the two most fatal years (FY2011 and FY2022) and deaths from all other years.

At least 167 deaths (including 5 mpd) due to floods have occurred in Australia from FY 2011 to FY 2022 (Table 1). Some 41 of the deaths (24.6%) occurred during FY2022 and 48 (28.7%) in FY2011.

Other high-flood-fatality years since 1900, apart from FY2011 and FY2022, include:

- FY1917 – 106 deaths (including 14 in VIC, Sep 1916; 66 in Clermont & surrounds, QLD, Dec 1916)

- FY1918 – 48 deaths (including 21 in Mackay & surrounds, QLD, Jan 1918)

- FY 1927 – 50 deaths (including 9 in Toowoomba, QLD, 1 Feb 1927; 27 in Ingham & surrounds, QLD, 9 Feb 1927)

- FY1930 – 48 deaths (including 22 in TAS, April 1929)

- FY1935 – 45 deaths (22 in VIC, Nov 1934)

- FY1946 – 47 deaths (including 11 in NSW, Jun 1945; 10 in QLD, Mar 1946)

- FY1950 – 48 deaths (including 12 in NSW, Mar 1950; 15 in NSW, Jun 1950)

- FY1955 – 41 deaths (including 25 in NSW, Feb 1955)

- Fy1974 – 42 deaths (including 14 in QLD {& NSW}, 25 Jan 1974 + 6 in NSW & QLD earlier in Jan 1974)

Most flood deaths have occurred in QLD (n=95; 57%), followed by NSW (n=48; 29%), throughout the record from FY2011 to FY2022. In FY2011, however, a much greater percentage of deaths, 85% (n=41), occurred in QLD, 10% in NSW and 4% in VIC. In FY2022, 58% (n=23) of deaths occurred in QLD, 39% in NSW and 5% in Victoria.

Of the 167 total deaths, 120 (72%) were male and 47 (28%) female. In FY2022, the relative percentages were similar, with 29 (71%) male and 12 (29%) female deaths; however, in FY2011 the ratios were much closer, with 28 (58%) male and 20 (42%) female deaths (not shown).

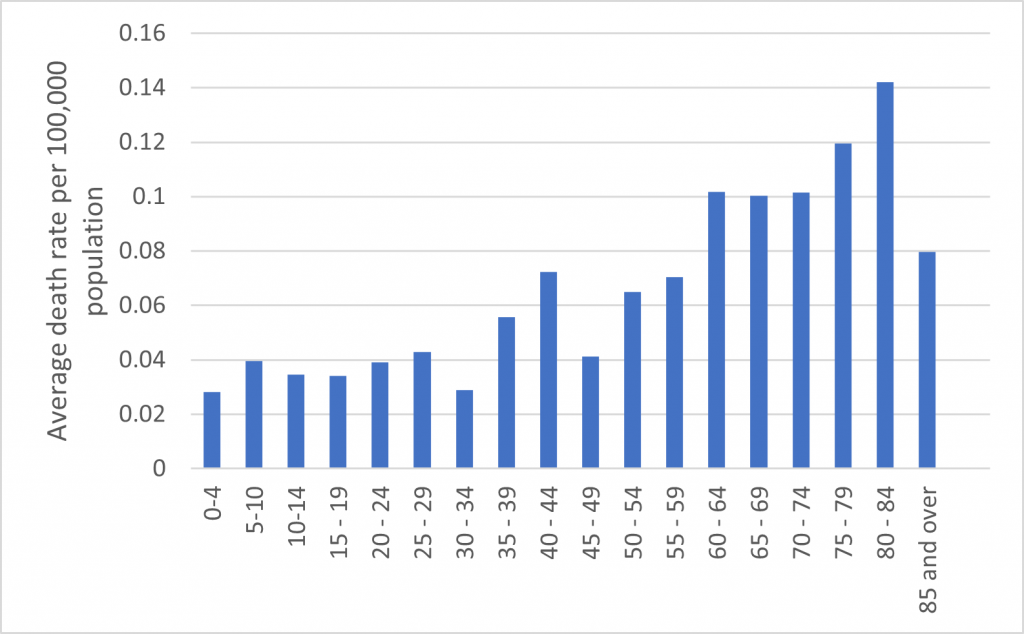

The most common age range of those killed in floods was 60-64 years (n=16; 10%) then 65-69 and 40-44 (both n=14; 8%), with deaths spread fairly evenly over most age ranges (Figure 3).

The normalised age ranges (Figure 4) show the 80-84 age group especially, but also those from 60-64 to 85 years and over, as overrepresented.

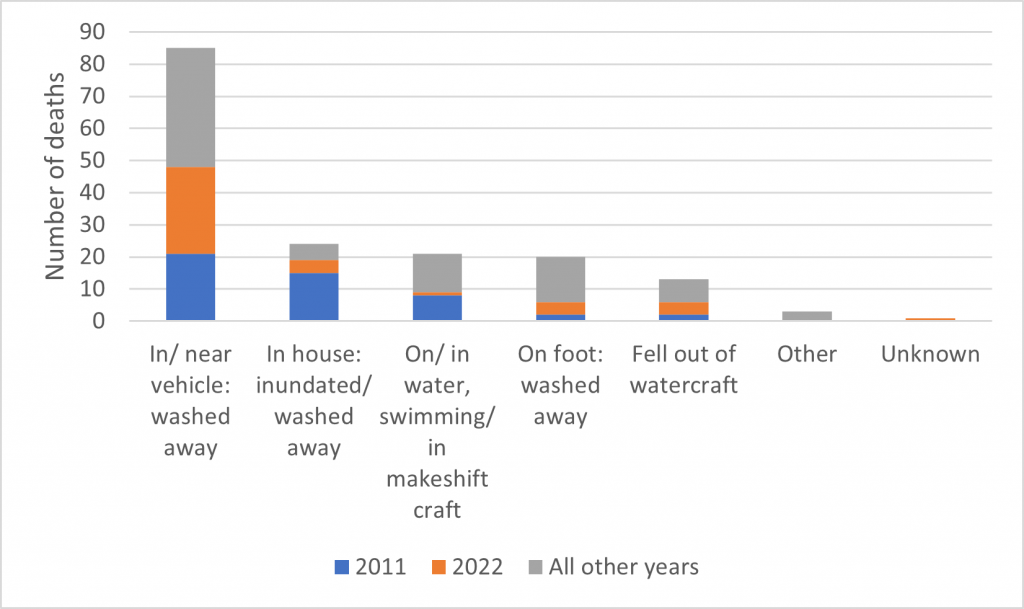

Half of all deaths (n=85) occurred in or near a vehicle that was washed away (Figure 6). Another 14% of deaths (n=24) took place inside or near a house that was flooded, washed away or collapsed due to floodwaters or rain-induced landslides. Almost as many deaths occurred when the person was on or in the water; either swimming or in a makeshift craft (n=21; 13%); and when the person was on foot and washed away (n=20; 12%).

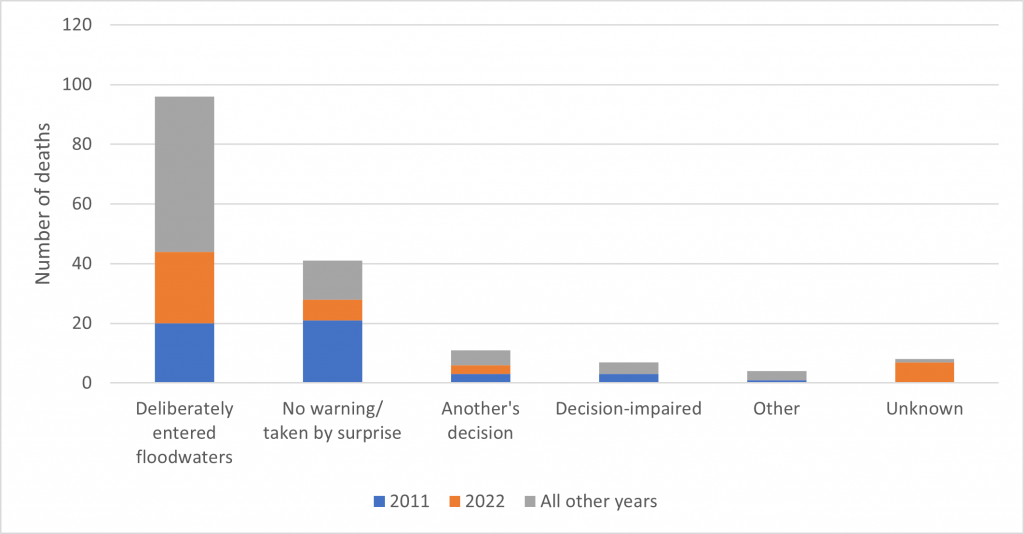

In relation to the action taken on the part of the decedents immediately prior to death, Figure 7 shows that 96 (57%) deliberately entered floodwaters and 41 (25%) either had no warning or were taken by surprise, either by the event or by the suddenness and/ or intensity (height) of the event. In 11 (7% of) cases, it was another’s decision: this relates to passengers in cars and, in this category, 7 (4% of) cases were deliberately driven into floodwaters, 2 were not and for the other 2 this data was unknown. Some 7 (4% of) cases were decision-impaired: i.e., the people were very young, mentally incapacitated, intoxicated or in some other state unable to make decisions.

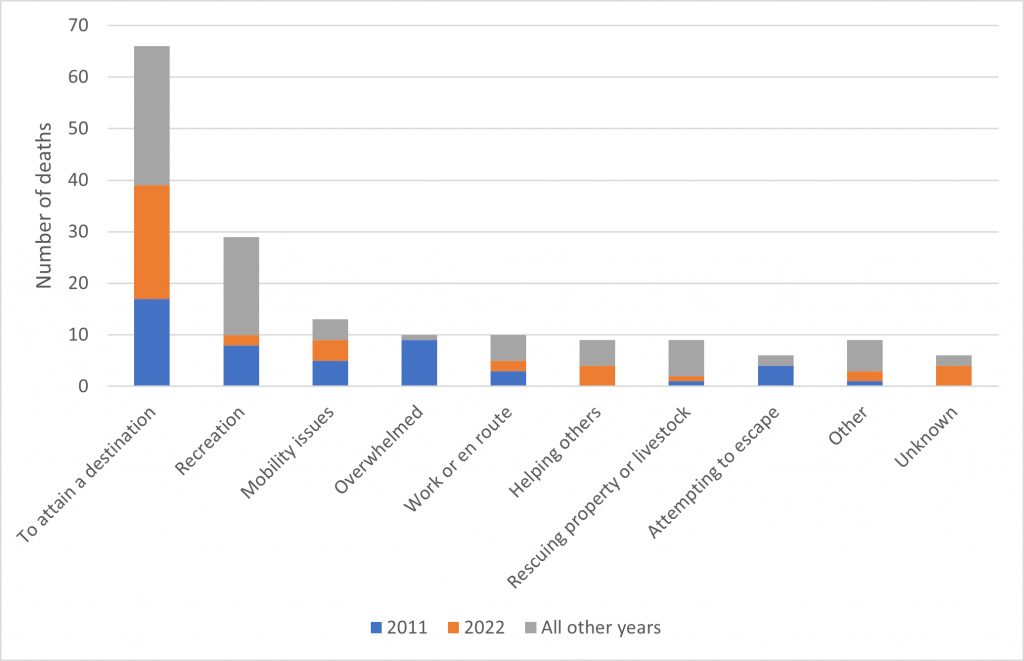

The most common reason behind the activity being carried out by the decedent was to attain a destination (n=66; 40%), followed by partaking in recreational activities (n=29; 17%) (Figure 8). A further 13 (8%) had mobility issues and 10 (6%), even though able, were overwhelmed by floodwaters (these two categories refer mainly to people who died in or near their houses). Another 10 (6%) were at work or enroute to work. Equal numbers of decedents (n=9; 5%) were either helping others or saving their own property, belongings or animals.

The PerilAUS record shows that the current focus of emergency managers for those most at risk of dying in a flood should be:

- Males (72% of fatalities)

- Persons living or travelling in Queensland (57%) or NSW (29%)

- Persons who attempt to drive through floodwaters (51%)

- Persons who deliberately enter floodwaters, either to drive through, recreate in or other (57%)

- Persons aged 60+ (38% of fatalities) or 50+ (52% of fatalities) years

- Persons whose motivation in entering floodwaters is to attain a destination (40%)

- Persons who use floodwaters as a recreational activity (17% of fatalities)

- Persons, especially the elderly and less mobile, whose house is situated at risk of major flooding (14% of fatalities)

The total of 40 deaths for the 2021/22 La Niña season (41 for FY2022 in total) is tragically high but could have been so much worse, were it not for the efforts of professional and volunteer rescue personnel and, especially, the ad hoc as well as organised actions on the part of the general public: it is a credit to all that the death toll was not much greater.

Amongst the 2021/22 incidents resulting in deaths were near misses: in the floods of November-December 2021 and January 2022 there were three instances of car-related deaths where a passenger or driver narrowly escaped the vehicle and an instance where two people escaped the fatal overturning of a tinnie. In the February-March 2022 floods, there have been three instances of car-related deaths where one passenger or driver narrowly escaped the vehicle and one instance where three people escaped.

There have also been many other narrow escapes and rescues of people, from:

- Cars driven into floodwater. For example:

- Greater Sydney, NSW, 7 March: Fire and Rescue NSW crews were deployed to Menangle Road in Campbelltown in Sydney’s south-west, where three cars were in floodwaters. They rescued two elderly occupants, trapped in one of the vehicles, minutes before the vehicle was engulfed by rising waters. Rescue tools were relayed to the vehicle so firefighters could break the car windows (SMH, 2022)

- Northern NSW, 24 February: Two Numulgi residents rescued an elderly man who had managed to climb to the top of his car, surrounded by fast-moving, rising floodwaters. He was distressed and wouldn’t leave his car. One, a retired trained rescue crewman for the local rescue helicopter, dived under the water and attached a strap to the car, which the other attached to their four-wheel-drive, dragging the car out of the water. The man was unable to respond with contact details for his family members but could only say, “I didn’t think it was that deep.” Because so many roads were cut off by floodwaters, it took time for emergency service help to arrive, and the man’s eventual retrieval was made possible only because one of the SES volunteers, a former work colleague, made arrangements, after a wade, for a vehicle and thence to Numulgi bridge, ~2km away, where the man was put into a dinghy and taken to rescue crews (ABC Central Coast, 2022)

- Queensland: A woman and her partner were pulled from their submerged car in Nundah, in Brisbane’s north after rescuers saw the light from her phone. The rescue crew responded when a car was washed into floodwater, but after almost half an hour wading in chest-deep water, there were no signs of life. A nearby resident called out and pointed to a light glowing in the water – the woman had been using it to send her last goodbyes to her loved ones. The crew dived under, smashed the car’s windows and discovered a man and woman inside. The crew got them to safety through more than 400 metres of floodwater (Brisbane Times, 2022)

- Houses engulfed by floodwaters. For example:

- Lismore, 28 February: Two elderly residents were stuck in their roof cavity, banging on the roof asking for help, with the water rising rapidly. They were dry but couldn’t see the situation unfolding. The husband descended to check damage and saw a rescue boat coming up the street, called out then they waded through chest high water to reach the boat. Many faced a similar predicament, stuck in roof cavities and attics with nowhere to go. Some were forced to cut through the roof to get out, and on social media, rescuers were urged to bring axes or saws with them to reach those stuck inside. Elderly neighbours were also rescued by private boat, the husband saying if it was not for local boat-owners, and a call out for private assistance by the Lismore Mayor, many would not have made it out (ABC Mid North Coast, 2022)

- Lismore, 28 February: Two local volunteers set out in a tinnie at 4am and saved more than 25 people over the course of four hours – including people on oxygen machines, people in wheelchairs and others with various disabilities (ABC News, 2022a)

- Lismore, 28 February: A police officer dived through an open window to rescue a 93-year-old woman in her flooded home, after NSW police and a team of SES volunteers, conducting search and rescue operations, heard a faint call for help from inside a home with water up to the eaves. The officer found the woman floating on a mattress, with no more than 20cm of room between the roof and the water level. The woman was pulled from the home on a boogie board, through the open window and onto a waiting rescue boat (ABC Mid North Coast, 2022)

- Areas devastated by rain-induced landslides. For example:

- Upper Wilsons Creek, 28 February: A couple were caught inside their home when it collapsed due to a landslide. The woman was trapped beneath rubble, both her legs broken; the man was knocked unconscious by the impact. When he came to, he managed to free his partner and they went to a neighbour’s house. A Mullumbimby paramedic and a community member hiked four hours through partially destroyed roads and landslides to treat the pair and bring them morphine, as there was no access for ambulance services. They spent 24 hours with the injured couple before they were rescued by helicopter, 38 hours after the house first collapsed (The Guardian, 2022)

- Upper Main Arm Valley, 28 February: NSW Ambulance paramedics and army reservists worked to free two people from rubble following a landslide at Motts Road, Upper Main Arm, west of Brunswick Heads. The reservists found a man up to his neck surrounded by mud, trees and branches before getting him out. The rescue operation remained underway into the night (ABC News, 2022b).

References

ABC Central Coast, 2022, Man dies in floodwaters on NSW Central Coast as drivers caught out in rising waters, Fri 25 Feb 2022, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-02-25/man-dies-in-floodwaters-on-nsw-central-coast/100860012, accessed 28/2/2022

ABC Mid North Coast, 2022, How elderly couple survived Lismore’s record flood inside their roof, Emma Siossian, Luisa Rubbo, Alexandra Jones, and Bronwyn Herbert, 1 Mar 2022, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-03-01/lismore-residents-recount-their-flood-ordeals-stuck-in-roof/100869384, accessed 4/3/2022

ABC News, 2022a, How Lismore locals became flood rescue heroes when emergency services were swamped, Tim Swanston and Paige Cockburn, Tue 1 Mar 2022, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-03-01/lismore-floods-how-two-blokes-in-a-tinnie-saved-25-lives/100869798, accessed 4/3/2022

ABC News, 2022b, Over-reliance on volunteers at the peak of the flood emergency in northern NSW must be addressed, locals say, Michael Atkin, 15/3/2022, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-03-14/mullumbimby-flood-response-over-reliance-volunteers-emergency/100903514, accessed 15/3/2022

Brisbane Times, 2022, Glowing phone led rescue crew to couple submerged in car, Cloe Read, 15 March 2022, https://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/national/queensland/glowing-phone-led-rescue-crew-to-couple-submerged-in-car-20220315-p5a4s4.html, accessed 15/3/2022

SMH, 2022, Elderly couple rescued from car ‘almost engulfed by water’ in Campbelltown, Sarah McPhee, https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/nsw-floods-live-updates, accessed 15/3/2022

The Guardian, 2022, ‘Next level destruction’: NSW residents detail the moments floods devastated their homes, Mark Isaacs, 6 March 2022, https://global-factiva-com.simsrad.net.ocs.mq.edu.au/ha/default.aspx#./!?&_suid=164740533366103084609100620115, accessed 16/3/2022

Click here to download a .pdf version of this briefing note.

About the author/s

Lucinda Coates

Lucinda is a Senior Research Consultant at Risk Frontiers. With over 30 years in the natural hazards field, she specialises in the impacts of and vulnerability vs resilience to hazard events. Highly experienced in data analysis, Lucinda also manages PerilAUS, an Australian database of hazard impacts.